Workers Party responds to consultation on adaptation to climate change in NI

Introduction

There are two main ways of thinking about responding to climate change. One approach, called mitigation, looks at how we could avoid future global heating. The other approach, adaptation, accepts that climate change is happening and looks at how we can prepare and adapt to the changes that are upon us. Both approaches are essential.

Under the terms of the Climate Change Act 2008 Northern Ireland Executive Departments have to produce programmes which set out their objectives, policies, proposals and timelines in response to the most recent UK Climate Change Risk Assessment (CCRA).

Since 2008, Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA) in Northern Ireland has developed a series of single coordinated adaptation programmes, which are known as Northern Ireland Climate Change Adaptation Programmes (NICCAP).

The Workers Party disagrees with the faith that DAERA has in finance and capital as agents of adaptation, arguing instead that the market has both produced the current environmental crises and is inherently unable to sustainably adapt to the crises. The Party also objects to the idea of assessing natural ecosystems as though they are commodities in a market, an approach known as ‘natural capital accounting’. The Party believes that successful adaptation and mitigation can only occur in a non-capitalist, socialist economy. Below, is the Workers Party response to the third NICCAP outlined by DAERA.

Part One: DAERA's Vision

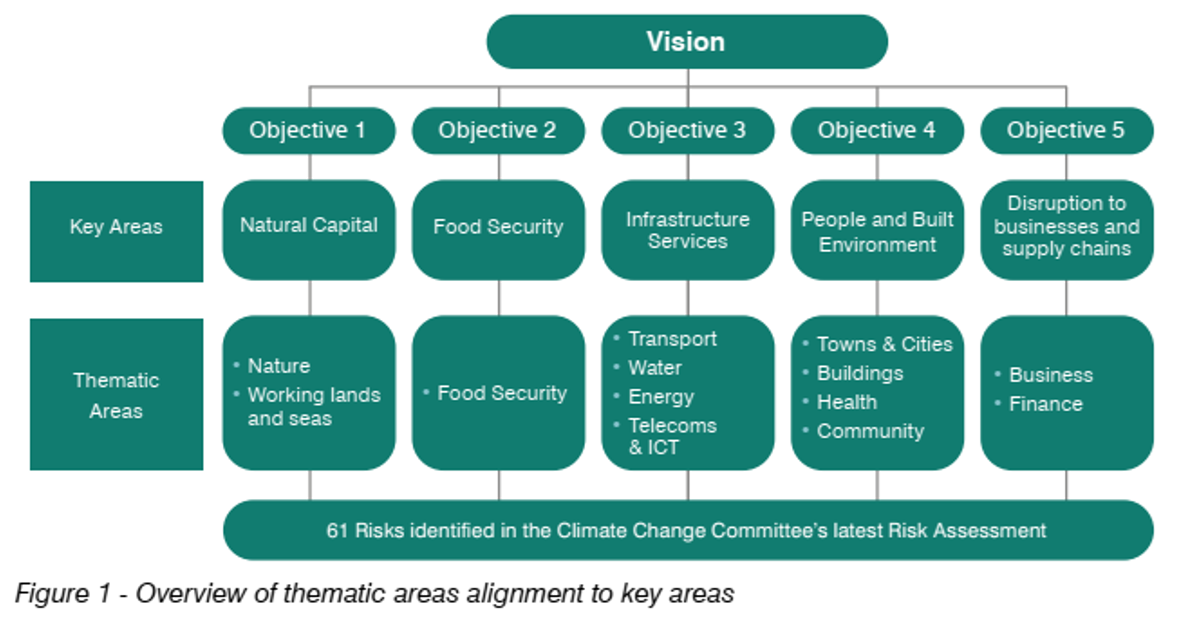

NICCAP3 outlines its ‘vision’ in the figure below. The Workers Party accepts the importance of most of the key areas but we argue that the ‘vision’ generally mischaracterises the role of business and finance, in particular they have a misplaced faith on market mechanisms as agents of future climate change adaptation. Below, the Party responds in detail to two questions about the 'vision'.

Do you agree with the approach taken to align the structure of NICCAP3 to the 13 thematic areas (covered above) used to assist in the future monitoring of adaptation progress in NI?

No, we don’t.

The Workers Party finds most of the 13 ‘thematic areas’ unproblematic. However, as a socialist Party, we believe that the current organisation of food security, energy, telecoms & ICT. transport, and private and outsourced healthcare under the ownership of a small number of capitalists and the anarchy of the market lead to disastrous outcomes for most people and for the environment.

In particular, the implication that business may simply need to undertake some changes to deal with risks to supply chains, access to capital and productivity impacts is based on a misreading of the role that capitalist enterprises have played in creating the current climate crises. Private enterprises are forced by market competition to ‘grow or die’. Due to this growth dynamic, global fossil carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in 2024 came to 37.4 billion tonnes, up 0.8% from 2023. Despite the urgent need to cut emissions to slow climate change, researchers say there is still “no sign” that the world has reached a peak in fossil CO2 emissions [1].

The Workers Party understands that climate change adaptation will not be easy. However, it has failed so far not because it is complex and challenging but largely because it has been and is based on market mechanisms. We agree with researcher Adrienne Buller, who states that “there is simply no example of a market-based transformation that comes close to resembling the scale and complexity demanded by the global replacement of fossil-fuel based infrastructure.” [2] The Workers Party believes that adaptation and mitigation measures can only be effectively carried out via democratic state ownership and direction.

The Workers Party fundamentally disagrees with the assessment of the natural world based on the notion of ‘Natural Capital’, and this is discussed further below. We also disagree with your horizontal depiction of ‘Key Areas’ in figure 1. As noted, the capitalist economy is key to the continuing growth of CO2 pollution. The endless growth required by competing business interests, means that global CO2 emissions will only decrease at the required rate in a non-capitalist economy.

Behind policies which aim to reduce CO2-eq emissions is the belief that capitalism can evolve towards a steady state, ‘dematerialised’ economy in which the environment is decoupled from economic growth. This is an impossibility, and working towards this business-as-usual future is worse than a waste of time because it leads people to think that the fundamentals of the capitalist economy can remain in place while pollution can be simultaneously reduced to a point of ‘sustainability’. In the words of Brazilian economist, Eduardo Sá Barreto according to the ‘green growth’ theoretical framework, “growth will always be possible, and our technological prowess will clean up our tracks”. Technological progress would be the main cause of the supposed decoupling between economic growth and material impact. In fact, while efficiency gains do create the possibility of saving resources and producing more with less, these efficiencies are inevitably used to foster continued growth. When resources are saved through greater efficiency, capital is released that previously operated in production. “This liberated capital must, at all costs, find othe opportunities to carry out its expansion logic. When it does, it necessarily re-establishes contact with” the material world. [3] And growth, and degradation, continue.

From the Workers Party perspective, adaptation to the effects of climate change must go hand-in-hand with the development of a new economy. Only an economy based on needs -and not the endless growth demanded by profit- can begin to lead us away from the chaotic and dangerous future that climate change will bring -and is bringing- to the world.

Do you feel that the vision, for a well-adapted NI, represents the ambition required to build a well-adapted NI?

No.

The Workers Party is in broad agreement with your description of environmental risks that climate change will bring to Northern Ireland in terms of flooding, heat stress, increased rainfall in winters, and hotter drier summers etc. We also agree on the importance of what you term ‘Nature Based Solutions’ such as afforestation, protecting coastal environments and peatland restoration.

Given our understanding that the current running of the economy and the disastrously wrong-headed mainstream belief that ‘green growth’ can be materially decoupled from the environment, a well-adapted Northern Ireland will, as elsewhere, require new economic formations based on democratic planning rather than the market. Unless we change direction, future generations will not thank us for our continued adherence to business-as-usual.

In relation to finance, the NICCAP3 argues that we will have to ensure “that systemic risks from climate change are minimised and it [‘finance’] can effectively support the economy in investing in necessary adaptation actions”. The idea that if risks related to climate change are minimised financial institutions will then be able to put the required money into adaptation programmes has not been borne out by decades of risk-averse financial dealings in the renewables sectors. Even with substantial state subsidies, the global financial sector has failed to make the investments which are needed to provide a habitable world without fossil fuels. This faith in the supportive role of finance is seriously misplaced.

Part Two: 'Natural Capital' and accounting for nature like it's money

These themes cover the natural environment and the role it plays in supporting life in Northern Ireland both through the habitats it provides for nature and the important role it plays in our local economy. Does the objective for Natural Capital provide the level of ambition required to meet the challenge of climate adaptation in this area?

No

As part of your objectives, you discuss creating “a climate resilient environment rich in the ecosystem services so important for human wellbeing and sustainable agricultural, forestry, fisheries and aquaculture sectors which are so important to the Northern Ireland economy”.

Political scientist, Alyssa Battistoni notes that global capitalist agriculture “diverts the material resources of a given region […] into the cultivation of a few kinds of profitable life: corn, wheat, cotton. […] Today 60 percent of land mammals [and 70 percent of birds] are livestock, and another 36 percent are human beings; only a meager 4 percent are wildlife.” [4]

Globally, the production of commodified food on an industrial scale has resulted in mass extinction of species and ecosystems. Over the past century, the ‘ecosystem services’ required by flora and fauna (and many millions of dispensable humans) have been destroyed in favour of “a few kinds of profitable life”. In the last forty years an estimated 50 percent of vertebrate wildlife has become extinct, and one million species are currently at risk of extinction.

In Northern Ireland, 75% of land is used for agriculture, with meat, dairy, and eggs the largest sectors, accounting for over 80% of agricultural output.[5] According to the 2023 State of Nature report “Northern Ireland is now one of the most nature-depleted countries on Earth”.

“Northern Ireland, like most other regions worldwide, has experienced a significant loss of biodiversity. … The evidence from the last 50 years shows that on land and in freshwater, significant and ongoing changes in the way we manage our land for agriculture and the ongoing effects of climate change are having the biggest impacts on our wildlife. At sea, and around our coasts, the main pressures on nature are climate change, marine development and unsustainable fishing”. [6]

The reality is that developments in capitalist agriculture and fishing have already significantly denuded the natural environment in NI. A properly sustainable, planned economy will endeavour to preserve as much of the natural environment as possible while meeting the needs of people in an equitable economy. Business-as-usual will lead to even further degradation.

The Workers Party strongly disagrees with the suggestion that environmental infrastructures can be viewed as ‘natural services’ and should be evaluated as ‘natural capital’.

We note that there is what seems to be a concerted effort among policy makers to ‘catch up’ with the rest of the UK by assessing environmental resources (termed ‘goods and services’) according to ‘natural capital’ accounting. In April 2025 the Research and Information Service in Stormont released a report called Public Estate Value to Society, which discusses ‘natural capital’ accounting in Northern Ireland. This paper also notes that the Environmental Improvement Plan commits Northern Ireland to adopting a natural capital approach.[7]

Public Estate Value to Society notes that “using monetary terms to value natural assets or ecosystem services does not necessarily promote the use of financial instruments to ensure their protection”. While NICCAP3 places no monetary value ‘ecosystem services’, the door is left open to adopting a monetary approach to environmental decision making.

Entirely adequate accounts of the natural environment can be given without need to place monetary values on natural phenomena. We note, for example, that the State of Nature Northern Ireland report provides a comprehensive description of the natural environment in NI without recourse to the language of natural capital.

Battistoni notes that “making ecosystems into revenue- generating property—let alone growth-stimulating assets—is, as we have seen, enormously complicated, and rarely successful. She describes how “public, private, and nonprofit sectors have constructed an elaborate labyrinth of social and economic institutions in service of making nature into credits, capital, or assets; buying and selling ecosystem services; pricing nature to save it”. Battistoni offers an alternative, non-commodified, approach:

Actually protecting ecosystem services, however, is much simpler. For the most part it just means preserving swathes of land large enough to keep ecological relations intact—and then leaving them alone. Why work so hard to make them monopolizable by private interests instead of embracing them as a public good? Why, put simply, should the state go to so much trouble to privatize and capitalize nature instead of socializing it? [4]

She quotes the philosopher Jacob Blumenfeld, who argues that our natural resources should be viewed as “sites of political contest and coordinated planning, so that non- monetary questions about the value of nature can even be asked in the first place, and proactively planned for in accordance with multiple criteria of human and non-human flourishing”. [8] Battistoni states:

To socialize nature would, then, bring political forms of decision-making and planning to bear on ecosystems rather than leaving them to the whims of the market preventing their conversion to sites of commodity production.

The Workers Party finds that a natural capital approach precludes the possibility of coordinated planning based on an always contested vision of natural resources as a public good.

References

[1] https://news.exeter.ac.uk/faculty-of-environment-science-and-economy/fossil-fuel-co2-emissions-increase-again-in-2024/

[2] Adrienne Buller, (2022) The Value of a Whale: On the illusions of Green Capitalism. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

[3] Eduardo Sá Barreto,. and Cunha, D. (2025) Marxism in the age of ecological catastrophe: Theory and praxis. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

[4] Alyssa Battistoni, (2025) Free gifts: Capitalism and the politics of nature. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

[5] https://friendsoftheearth.uk/latest/food-and-farming-northern-ireland

[6] Report available here: https://stateofnature.org.uk/countries/northern-ireland/

[7] Charlotte A. Hodges, (2025) Public Estate Value to Society

Available here: https://www.niassembly.gov.uk/globalassets/documents/raise/publications/2022-2027/2025/aera/3725.pdf

[8] Jacob Blumenfeld, “The Socialization of Nature,” ICI Politics of Nature Conference, Berlin, October 20, 2022.