Response by the Workers Party to Northern Ireland Climate Action Plan

The Stormont Government’s proposed action plan to tackle fossil fuel emissions is based on the idea that market mechanisms can reduce emissions to ‘net’ zero and lead to a future where capitalism can operate ‘as usual’ while at the same time fossil fuel emissions are reduced to zero or nearly zero and energy is produced from renewable sources, i.e., wind and sunshine. They bring together a number of mainstream eco-capitalist notions to convince the NI electorate that this magic trick is possible. In what follows, the Workers Party argues, with evidence, that only a socialist society can produce the outcomes that future generations will need if humanity and the world is to flourish.

INTRODUCTION

“…we know that achieving these reductions will be a significant challenge and the [greenhouse gas] reductions of 18% we have achieved in the last 31 years (compared to the 1990 baseline) highlight the scale of the challenge ahead in the coming 29 years. In the next decade the fact we have to do almost twice as much as has been achieved to date in less than a third of the time means that we need a fundamental change in our approach. We must take action urgently”.

NI Executive, Green Growth Strategy, 2021

The Workers Party agrees that urgent action is required to significantly reduce CO2e emissions. However, the Green Growth agenda outlined in the NI Climate Action Plan (henceforth, NICAP) cannot produce the required changes on a global scale because the growth imperatives of capitalism cannot possibly result in the kind of ‘dematerialised’ society that green growth theorises and that NICAP implies, a world in which private ownership of competing business interests can somehow coexist with a decrease in output.

Climate Change, Global emissions, and Profitmaking

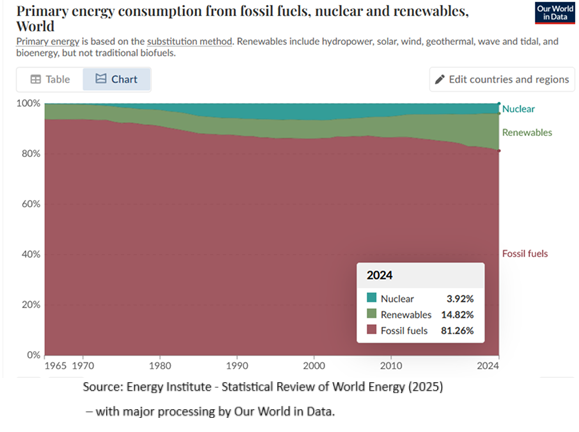

The speed and scale of the energy transition we need today in switching from fossil fuels to low-carbon energy represents an unprecedented challenge. Based on the ERA5 climate dataset, 14 of the 23 months from September 2023 to April 2024, and from October 2024 to March 2025, global surface temperatures were substantially above the projected limit of 1.5°C, ranging from 1.58°C to 1.78°C. It is clear to the Workers Party that this radical challenge demands radical responses. In spite of the objective need for radical change, we have seen decades of market-based attempts to significantly lower the amount of fossil fuels polluting the atmosphere by steering private industries towards renewables, so that in 2024 global primary energy consumption from fossil fuels stood at 81%.

Since the early years of this century, the two main market-based approaches to lowering Co2e pollution have been (1) carbon trading and (2) incentivising private-sector investment in renewable energy, green technologies, and other low-carbon solutions. Despite the growth of renewables-based energy production in western Europe and the UK, both of these approaches have failed to lower global fossil fuel output. Both of these are discussed below in relation to NICAP.

Data from the International Energy Agency show that global energy consumption rose at a faster-than-average pace in 2024, resulting in higher demand for all energy sources, including oil, natural gas, coal, renewables and nuclear power. Globally, there is no sign that national policies or multilateral agreements have reversed the growth of polluting fossil fuels in favour of renewables.

According to the 2025 Production Gap Report, “governments, in aggregate, still plan to produce far more fossil fuels than would be consistent with limiting global warming to between 1.5ºC and 2ºC.” The Report notes that in aggregate, governments plan even higher levels of coal production to 2035, and gas production to 2050, than they did in 2023. Planned oil production continues to increase to 2050. This destroys any expectations that demand for coal, oil, and gas will peak before 2030: the continued collective failure of governments to curb fossil fuel production and lower global emissions means that future production will need to decline more steeply to compensate. “Reaching net zero greenhouse gas emissions in the second half of the century, as the Paris Agreement calls for, will require cutting fossil fuel production and use to the very lowest levels possible. Achieving these reductions will require deliberate, coordinated policies to ensure a just transition away from fossil fuels. While a few major fossil fuel-producing countries have begun to align production plans with national and international climate goals, most still have not.”

For the Workers Party it is clear that the capitalist imperative for continuous growth is incompatible with production plans aligned with planetary requirements. That is why it is unsurprising that in 2022, the UK government, purveyor of the ambitious GHG reduction plans mentioned in NICAP opened a licensing round for companies to explore for oil and gas in the North Sea, with 100 licenses for nearly 900 locations are being offered for exploration. According to the BBC, “the decision is at odds with international climate scientists who say fossil fuel projects should be closed down, not expanded. They say there can be no new projects if there is to be a chance of keeping global temperature rises under 1.5C”.

Renewables

Taken in isolation, the growth of solar and wind power has been impressive. In its “Electricity Mid-Year Update 2025”, the International Energy Agency notes that the combined share of solar PV and wind energy in global electricity generation are forecast to grow “from 15% in 2024 to 17% in 2025, reaching almost 20% by 2026 – a near-fivefold increase from just 4% a decade ago”. However, as the graph below shows, energy consumption remains massively based on fossil fuel sources and the gradual development of renewables sector has occurred during a period of steadily increasing GHG emissions as energy consumption has grown. In 2022 the business magazine Forbes noted that “while renewable power expanded at record rates, fossil fuels maintained an 82% share of total primary energy consumption” down 5% from their 2010 share of 87%. Robert Rapier from Forbes noted drily that “at that rate of decline, it would be nearly 200 years before fossil fuel consumption reached zero”. Given that the world crises demand immediate action, the gradual, if relatively impressive, growth of the renewables sector under market conditions will not produce the results we need.

NORTHERN IRELAND CLIMATE ACTION PLAN

It is within the context of enormous private profit with institutional support, continued environmental destruction and emissions, that the green growth ideology that underpins NICAP must be seen. Below, we discuss the shortcomings of aspects of the green growth agenda seen in NICAP.

Circular Economies

The circular economy offers an alternative to our current linear take-make-use-dispose approach to using resources. In a circular economy we: • rethink and reduce our use of Earth’s resources; • switch to regenerative resources; • minimise waste; and • maintain the value of products and materials for as long as possible by reducing, reusing and recycling. NICAP 3.6

The idea of the circular economy makes good sense in many ways. However, the make-use-dispose approach to using resources is in perfect alignment with the growth imperative of capitalist economies. Similarly, innovations leading to increased efficiency in production and Increased efficiency leads to higher output by workers without the need for a corresponding wage increase. This leads to extra profit in the hands of the owners of businesses, much of which is inevitably put in to increasing productivity. Thus, the outcome of these efficiency gains is not a reduction in material resource usage or impact. Instead, the pursuit of greater profit through efficiency ultimately drives an increase in the overall physical scale and intensity of production.

In The Impossibilities of the Circular Economy , Reinier de Man argues that the 'circular economy' framework, built upon principles like 'waste is food,' is fundamentally flawed from both a technical and scientific standpoint. This conceptual weakness poses a policy hazard, as it promotes unrealistic visions of a rapid, waste-free transition and consequently denies the scale of systemic interventions truly needed for sustainability. De Man concludes that “oversimplified and therefore misleading fairy tales of a rapid transition to a circular economy … deny the seriousness of the problem and the difficulty of its solutions. … Policy makers should no longer be misled by empty slogans such as ‘circular economy’. They should focus on real problems, real developments and real solutions in the real world instead of ideal solutions in an idealised world. Instead of dreaming about unlimited green growth in a waste-free world, they should focus on the intelligent design of products, production and recycling processes and minimisation of natural resource use.” The Workers Party agrees with this assessment and in our view the real-world solution to production and recycling can only be found in socialism.

Market Failure

Market conditions must be attractive, and investments must be enabled by creating routes to market, facilitating partnerships and addressing disincentives to invest while at the same time ensuring that there is fair access to opportunity for all.

One such funding mechanism, identified by DoF, which has been in place since 2017, is the Northern Ireland Investment Fund (£150 million), which aims to help address market failures and accelerate and increase investment in private sector-led development, including infrastructure and low carbon projects. NICAP 1.3.3

From the Workers Party perspective, climate change mitigation will not be easy, but it has failed so far not because it is complex and challenging but largely because it is currently based on market mechanisms. The concept of ‘market failure’ is a key ideological underpinning of green capitalism.

Market Failure theory is based on the fact that capitalist production makes use of natural materials as ‘free’ gifts of nature, either as production sources (such as minerals, plants, animals, oil) or as sinks, i.e., waste deposits (such as dumping grounds, rivers, the seas, the air). The argument goes that because pollution is unpriced, market actors (capitalists) currently have no incentive to discontinue using (and abusing) the resources of nature either as sources or sinks. Market failure theory says that a price should be put on nature’s free gifts so that the natural environment can be subject to capitalist efficiencies.

The state’s role, as seen in the quotes from NICAP above, is to encourage businesses to move away from fossil-fuel based

production to production based on renewable and other ‘green’ energy sources, either by threats and punishment (fines and taxes for polluters) or through subsidies, preferential or concessionary financing, or favourable long-term contracts for companies developing or using non-fossil fuel energy sources.

The ‘market failure’ theory says that the price mechanism and competitive innovation between capitalists will reach the desired outcome of zero or ‘net zero’ emissions and climate stabilisation more ‘elegantly’ and efficiently than direct state involvement could. As a result, ‘inefficient’ and ‘old-fashioned’ state utilities should be forced to make way for a new generation of ‘disruptive’ green energy companies.

Activist and author Adrienne Buller notes that “misplaced emphasis on the efficiency achievable through the price mechanism ignores that some forms of carbon reduction are far more durable, effective (inasmuch as they swiftly and directly reduce emissions) and just than others. There is simply no example of a market-based transformation that comes close to resembling the scale and complexity demanded by the global replacement of fossil-fuel based infrastructure.”

Emissions Trading Systems

Emission Trading Schemes (ETS) are an important carbon pricing instrument. In the UK and EU, they act as strong policy levers for driving down GHG emissions in energy intensive industries and the aviation and power sectors. They work on a ‘cap and trade’ principle, where a limit is set on the total amount of certain GHG that can be emitted by sectors covered by the schemes. This restricts the total amount of carbon that can be emitted and, as the cap is decreased over time, can make a significant contribution to achieving the net zero target. 1.3.4

During the carbon budget period, DAERA will work closely with the EU and UK to ensure that the Northern Ireland position is reflected in the design and implementation of the ETS.

As soon as the European Union fully rolled out its ‘Emissions Trading System’ (EU ETS), the world’s largest emissions trading market, in 2008, it was plagued by serious problems. In its early days, far too many permits were given out and power companies and energy intensive industries gained billions in windfall profit—profits that, as TUED researchers note “mostly turned into shareholder dividends, with little invested in new clean energy infrastructure.”

The Heinrich Böll foundation notes, “brought in with the aim of providing a price signal that would help cut greenhouse gas emissions, the trading scheme became a cash cow for the EU’s largest emitters of greenhouse gases. Instead of incurring additional costs in accordance with the ‘polluter pays’ principle, the scheme provided substantial profits for the largest emitters of greenhouse gases in Europe: a comprehensive study showed that between 2008 and 2014 they amassed assets worth more than eight billion euros from the sale of surplus emission certificates they received free of charge”.

In recent years the price of carbon on the EU ETS has started to rise. But the EU accounts for only 5.9% of the world greenhouse gases (GHGs). Moreover, within Europe the EU ETS covers roughly 45% of the EU’s economy, amounting to around 4% of the world’s GHGs. Although it has been 20 years since the 2005 launch of the EU ETS, and there are now other ETS systems operating around the world (mostly in rich countries), the vast majority of global emissions (77%) are still not priced at all in 2024, and according to the Institute for Climate Economics “the share of global emissions covered at an effective price … has remained at 6% since 2023”. It is perverse to argue that such a flawed and weak market mechanism can govern radical reductions in pollution by private enterprises. Northern Ireland should lead the way by providing democratic state control over the energy supply.

A new Renewable Electricity Support Scheme and Contracts for Difference

Proposal: A new Renewable Electricity Support Scheme (jointly quantified in the 80% of electricity consumption from renewable energy by 2030 target).

The development and delivery of a new support scheme will be an important driver to achieve the legislative target to increase renewable energy. In the rest of the UK, Contracts for Difference has become the main mechanism for supporting low carbon electricity generation.

A new Renewable Electricity Support Scheme in Northern Ireland is aimed at encouraging investment in local renewable electricity projects whilst also protecting consumers from global price shocks. Such a scheme would also support trade and investment in Northern Ireland, driving improvements in wealth, prosperity and living standards across the country. Establishing the main mechanism for encouraging investment in renewable electricity in Northern Ireland, a new support scheme would be the catalyst to lower carbon emissions and grow the green economy, including growth of jobs that are climate resilient. NICAP

In theory Contracts for Difference (CfDs) provide renewable energy developers with guaranteed fixed prices, which lowers their financial risks and attracts investment, while helping keep costs down for both the government and consumers. To manage what consumers pay, the government imposes a maximum bid price; any project quoting above this limit won’t be awarded a contract. However, rising supply chain costs and higher interest rates have pushed renewable project expenses up, making it harder for bids to meet the cap price and make a profit. As Greenpeace UK notes, “ despite offshore wind remaining far cheaper than the default alternative (fossil gas generation), it’s unlikely that developers will be able to bid at prices under the cap price – resulting in no bids”.

This structural issue has led to failed auctions around the world. For example, energy auctions in Asia and the UK, have recently struggled to deliver projects as planned, largely due to shifting market forces such as rising inflation and increased financing costs. In Asia, renewables auctions have faltered as project costs outpaced government-set price caps, leaving many initiatives economically unviable. Similarly, in the UK, recent Contracts for Difference (CfD) auctions revealed that offshore wind developers refrained from bidding, citing government strike prices that fail to reflect soaring costs, including inflation and higher interest rates. As one industry expert told the BBC, “the cap prices simply do not reflect the reality of soaring supply chain and financing costs, making many projects unviable.”

This mismatch between fixed subsidy caps and low profit margins has resulted in fewer bids and unmet renewable capacity targets, as seen in floating wind projects in Cornwall where only two-thirds of the auction target was achieved. As noted by the Financial Times, “developers had repeatedly warned that support on offer was too low to offset their rising costs”. In response, the UK government is moving to reform the CfD scheme by relaxing planning requirements and extending contract terms, aiming to better align subsidies with market demands (Reuters). These developments highlight the growing challenge of balancing policy frameworks with volatile market economics to ensure renewable energy expansion does not stall. But the potential for continued crises and destabilising ‘reforms’ highlight the structural problems of governments trying to please risk-averse capitalists and keeping prices low enough to ensure consumer buy-in. State controlled democratic ownership and development of renewables will place sustainability and public need at the centre of all decision-making on renewable energy, without having to meet the needs of a small group of profit-seekers.

ALTERNATIVE POLICIES

The Workers Party proposes the following responses to the climate emergency that our world faces.

The nationalisation of energy production and the energy infrastructure. This would mean that energy policy can be democratically decided without factoring in the profit-making imperative that capitalism demands.

A cheap/free at the point of demand modern transport infrastructure.

Fisheries and waterways to be publicly owned and sustainably managed.

Food production to be driven by need rather than profit.

Factories to produce for need not for profit.

Construction based on needs not on profits.

These policies are based on the clear recognition that technology alone cannot mitigate the environmental crises. What is required is a fundamental change in social relations, i.e., in the way goods and services are produced and in the way that the social surplus is used. To make these changes we will need to build socialist society.