Green Growth Ideology and Eco-Communism

by Workers Party Research Section

PART TWO OF A TWO-PART SERIES

Preface

The final section of this two-part series, explores the necessity of moving beyond capitalist logic to address the global environmental crisis. It argues that the inherent drive for capital accumulation under capitalism makes sustainable "decoupling" of growth from emissions impossible, suggesting instead that a system of social ownership and society-wide planning offers a more viable path for humanity.

The text outlines a strategic vision for the left, specifically recommending that the Workers Party continue to develop detailed policies to counter "green capitalism."

Key proposals include:

Nationalisation and Infrastructure: Nationalising energy production and providing free or low-cost modern public transport.

Production for Need: Shifting the focus of factories, construction, and food production from profit-driven models to those based on societal needs.

Global Solidarity: Recognizing Ireland’s role in the imperialist world system and advocating for a CO2 budget that accounts for the "super-exploitation" and environmental vulnerability of the Global South.

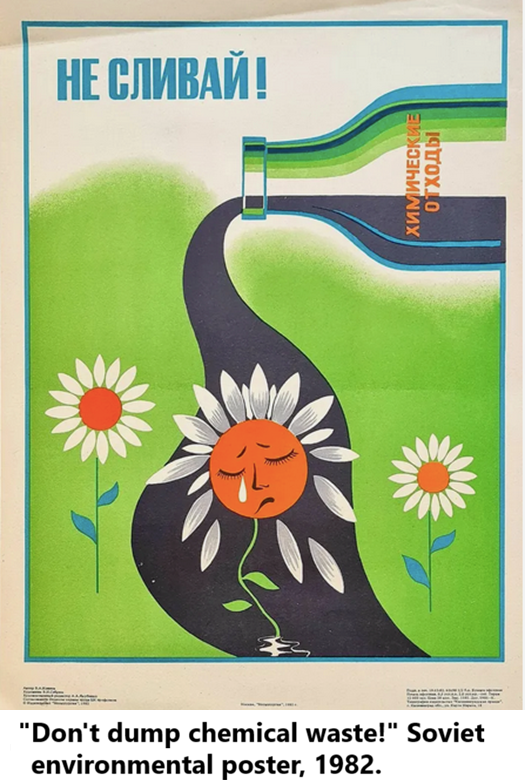

The article also challenges mainstream liberal and Trotskyist critiques of "actually existing socialism," which often dismiss the environmental records of states like the Soviet Union as unmitigated disasters. Drawing on the work of geographer Salvatore Engel-Di Mauro, the text highlights positive environmental outcomes achieved during the Soviet period—such as low per capita consumption, prioritised public transit, and extensive urban green spaces—despite the pressures of rapid industrialisation.

The Workers Party contends that a fundamental change in social relations is required to realistically mitigate the environmental crisis.

Strategies for the left

Under the current system, competitive pressure forces capitalists to accumulate capital, which in turn leads to economic growth. Growth, which cannot realistically be ‘decoupled’ from energy consumption, results in increased emissions on a global scale. While the imperialist countries, may see some decline in emissions, the products and raw materials that they import are made in countries where emissions continue to be high. Unless the economic logic of capitalism is removed, any reduction of emissions intensity of GDP will be offset by the economic growth endemic to the system.

Can some form of ‘market socialism’ work where capitalism fails? Regardless of the limits that ‘market socialism’ might place on the power of capital, so long as the market is the dominant mechanism of exchange and distribution, it will impose constant pressure on business enterprises (including cooperatives, and state-owned enterprises run as business) to accumulate capital and to expand.

In the absence of the market, society-wide allocation of productive resources can be carried out based on planning. Under an economic system based on social ownership, society-wide planning can be used to allocate the surplus product for purposes other than commodity production and profit making. The social surplus, produced by workers, currently goes into the pockets of capitalists, and is invested towards the accumulation of further profits. Under a system of society-wide planning the social surplus may be used for decarbonization, environmental projects, or in other ways that help to advance the wellbeing and potential of the people. Planning is not an easy process. Who will do the planning? What will be the extent of democratic input to the plan and how will democratic input be achieved to meet complex ends? These questions aside, as Chinese Marxist Li Minqi notes, “a system based on social ownership of the means of production and society-wide planning probably offers the best hope for the humanity”. [15]

Socialist environmental policies should call for:

· The nationalisation of energy production and the energy infrastructure

· A cheap/free at the point of demand modern transport infrastructure

· The end of Ireland’s role as an export platform for USA/UK multinationals, which includes an end to the tax holiday for MNCs.

· Opposition to profit-driven pharmaceuticals

· Research and development in Ireland’s universities should reflect the needs of Irish people not the profits of MNCs

· No to biofuels and other false promises

· Fisheries and waterways to be publicly owned and sustainably managed

· Food production to be driven by need rather than profit

· Factories to produce for need not for profit

· Construction based on needs not on profits

· Recognition of Ireland’s place as a dependent country in the current imperialist world system which has led to impoverishment and super-exploitation [16] of the Global South. Recognition that people in the Global South, who are least responsible for GHG emissions, are feeling the worst effects of global heating and other environmental disasters. The remaining CO2 budget should be divided up based on this recognition.

These and all policies should be based on the clear recognition that technology alone cannot mitigate the environmental crises. What is required is a fundamental change in social relations, i.e., in the way goods and services are produced and in the way that the social surplus is used.

The Socialist states and the environment

What lessons can we learn from the environmental practices of the Soviet Union and the other socialist states? For mainstream liberals the socialist states were an unmitigated environmental disaster. For liberal and Trotskyists ‘Soviet communism’ is synonymous with the worst environmental carnage the world has ever seen. According to one scholar, “the environmental disasters of the Soviet Union illustrate the inevitable self-destructive tendencies and uncontrollable dynamics of any society that attempts to reduce people and nature to mere instruments of production”. [17]

In similar vein, Martin Empson of the Socialist Workers Party UK states that, “the accelerated industrialisation that Stalin imposed on the Russian economy destroyed the lives of millions of people. It also involved the ruthless degradation of the natural world. For Stalin and those who formed his bureaucratic ruling class, the environment was something to be utilised for his ends” (18).

Australian Trotskyist, Renfrey Clark goes even further, declaring that “the damage done to the environment by the Soviet regime and its successor doesn’t remotely bear comparison with that in the West. It was, and remains, catastrophically worse. Particular countries elsewhere, especially in the developing world, have suffered one or another ecological disaster, sometimes of mind-bending dimensions. The USSR managed something in just about every sector of heavy industry to match the worst of them.” [19]

If all this is true, there are no positive lessons to be learned from the ways that the environment was managed in the Soviet Union (and in present-day Cuba). But the Liberal and Trotskyist representations of State Socialist environmentalism are cartoonish parodies. For Trotskyists, ‘actually existing socialism’ is a form of capitalism and/or a degenerated system that failed to turn socialist. According to this purist perspective, real socialism will be a state where social and ecological harmony will almost magically prevail, “a society in which the division between organizers and organized had been overcome; that is, … a genuinely democratic society. Under these conditions people would freely choose their futures. This would have been real communism. Whether this social form would have inspired and enabled people to develop their economies without destroying their environments is still an open question. It has not yet been tried.” [17]

Naïve fantasies aside, the socialist states inherited widespread social deprivation and environmental devastation, and many had long been looted by colonising liberal democratic empires. As Michael Parenti notes, “the pure socialists oppose the Soviet model but offer little evidence to demonstrate that other paths could have been taken, that other models of socialism—not created from one’s imagination but developed through actual historical experience—could have taken hold and worked better. Was an open, pluralistic, democratic socialism actually possible at this historic juncture? The historical evidence would suggest it was not”. [20]

In his important book, Socialist States and the Environment (2021), geographer Salvatore Engel-Di Mauro describes some of the environmental positives of the socialist states. In state-socialist countries inheriting a lack of basic sewerage collection and treatment infrastructure, the introduction of water purification plants led to greatly improved public hygiene. In cities, public transportation was privileged over private vehicle use.

City planning included the provision of ample green spaces. Housing was centrally planned and largely guaranteed, all of which contributed to reducing urban expansion pressures and keeping air pollution sources in check. Per capita resource consumption was relatively low, and recycling was routine. Attempts to mitigate air pollution in the socialist states included switching to natural gas where feasible and retrofitting industrial plants with less polluting equipment. Through international treaties, socialist states also promoted biodiversity protection, air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions reduction, and soil conservation worldwide.

There were some disastrous environmental impacts under state socialism. For example, air and water pollution from industries were problematic especially in conditions of rapid industrialisation. Other examples of major environmentally destructive aspects to Soviet socialism derived from the introduction and expansion of mining, fossil fuel production and use, and mechanised farming with intensive use of agrochemicals. However, these negative environmental effects are not confined to socialist states and are encountered in capitalist countries and in particular in countries reliant on raw material exports and/or intermediate manufacturing products.

These negative environmental impacts were not intrinsic to state socialism. In contrast, the growth imperative and exploitation are intrinsic to capitalism.

On the whole, during their existence the socialist states, were able to expand or retain natural habitats , keep consumption levels low, build cities that were environmentally more sustainable than those in the industrialised capitalist countries, and monitor and contain air pollution.

All these environmental achievements occurred while the socialist states were under immense pressures from within and without. In contrast, when China began to regress to capitalism in the late 1970s there was an obvious intensification and expansion of environmental damage. As such, the PRC is, as Engel-Di Mauro says, “a showcase for the effects of an arrested state-socialist path redirected to a form a capitalist economy”. [21]

Rather than mischaracterising and jettisoning state socialism as the liberals and Trotskyists do, the Workers Party draws inspiration from such historical experiences and achievements and the current reality of socialist Cuba, while recognising the problems that persisted. Such a perspective will help workers make decisions about the environment that are both realistic and revolutionary.

References

[15]Li Minqi, Anthropocene, Emissions Budget, and the Structural Crisis of the Capitalist World System Journal of World-System Research | Vol. 26 Issue 2, 2020

[16] On super-exploitation, see John Smith, ‘Imperialism in the Twenty-First Century’, Monthly Review ,Vol 67, No 3, July/August 2015

[17]Arran Gare, ‘The Environmental Record of the Soviet Union’ , Capitalism Nature Socialism, 13 (3), September, 2002

[18]Martin Empson, Land and Labour, Bookmarks, London, 2014

[19]Renfrey Clark, Socialist Alliance, Australia 2011, our emphasis https://socialist-alliance.org/alliance-voices/ecological-disaster-was-ussr-0

[20]Michael Parenti, Blackshirts and Reds, City Lights Books, San Fransisco, 1997 pp51-2

[21]Salvatore Engel-Di Mauro, Socialist States and the Environment, Pluto Press, 2021