1970s to 1990s

Until 1977, local government water services in Ireland were paid for under domestic rates paid by householders. Pressure on political parties to address domestic rates had grown as rate bills, payable as a lump sum, increased substantially in the context of mid-1970s inflation.

After an election in 1977 the new government abolished domestic rates by transferring liability from the householder to central government via a ‘domestic rates grant’ paid to local authorities.

The 1980s economic crisis meant this new regime quickly failed due to the prolonged recession (1980-1987), which saw falling living standards, a dramatic increase in unemployment and, rising emigration once again. Total employment declined by almost 6 percent and employment in manufacturing by 25 percent. In this context, in 1983 the central government provided local authorities with the power to levy charges for water, which most local authorities accepted. This move prompted resistance by householders, who correctly saw charges as a double payment in a climate of recession and tax increases.

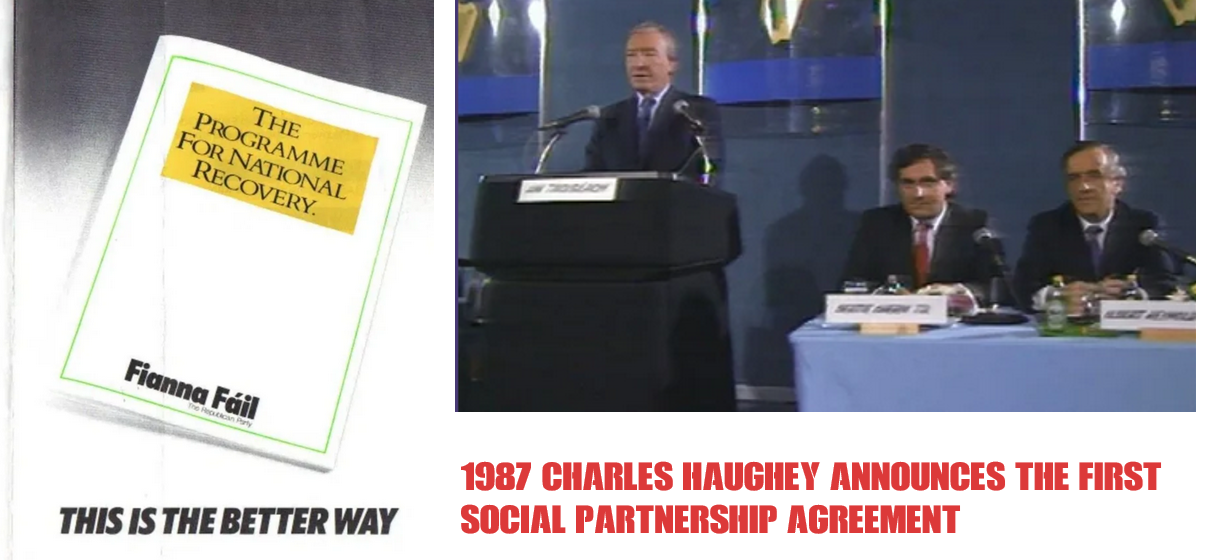

Social Partnership

1987 saw the first of what would be a series of corporatist 'social partnership' agreements agreed between the Government, the main employer groups and the trade unions under the leadership of the Irish Congress of Trades Unions (ICTU) in which a trade-off of modest wage increases was granted in exchange for a lighter income tax burden on business. Between 1987 and 2009, social partners concluded seven tripartite social pacts.

Social partnership, always an illusion, effectively collapsed at the end of 2009 when the Government imposed income cuts of between 5% and 8% for about 315,000 public servants in its Budget. The fact that Irish trade unions were locked in to a social-corporatist arrangement with government and employers for more than two decades might explain their inability to conduct a sustained campaign against the austerity politics which followed the economic collapse of 2008, which the attempt to force water charges was a part of.

1990s Market Environmentalism

The 1992 International Conference on Water and Environment convened in Dublin and enshrined ‘market-environmentalist’ thinking on water provisioning in the Dublin Statement on Water and Sustainable Development. Market environmentalism is an ideological construct which attempts to justify the privatisation of public utilities on the understanding that capitalist relations will ensure that resources are efficiently used, that price discipline will prevent overuse of scarce resources.

According to this framing, the state is berated for its neglect of water services infrastructure, and public funding and management are said to be inherently inefficient. As with ‘green growth’ and other reactionary ideological constructs, the language of environmentalism is appropriated by financial concerns so that concept of sustainability now applies as much to how water services are financed as it is used to refer to the sustainable use of a natural resource. The Irish state, the IMF, and the EU all endorse this approach to the use of natural resources, and this underlies the attempt on the part of the Irish state to introduce water charges.

In November 1992, Tomás MacGiolla, sole remaining Workers Party TD (MP) after a split with social democrats, warned that "in Thatcher's Britain, when little else was left in public hands, even water was privatised. Ireland's Thatcherites in Fianna Fail, Fine Gael and the Progressive Democrats will do the same."

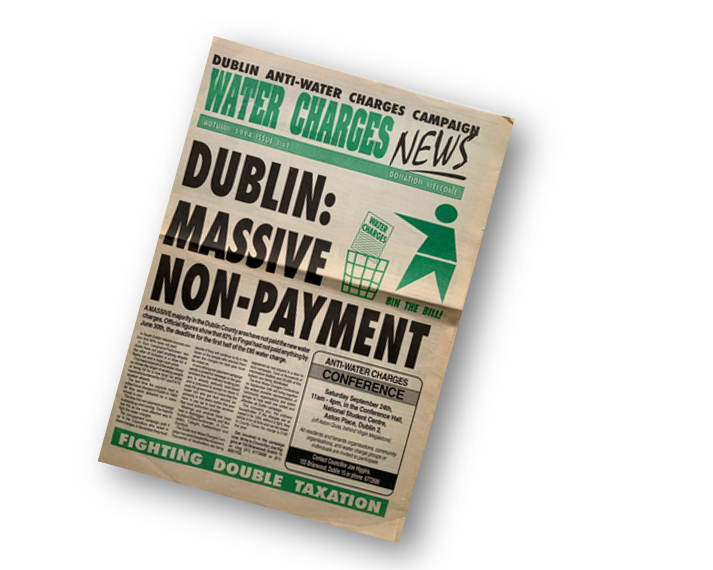

The first signs of public opposition came in 1994 when the introduction of water charges by Dublin City Council was met with demonstrations and boycotts. In September 1994, a Dublin Anti Water Charges Conference was organised to develop a joint campaigning strategy for those opposed to the water charges and was attended by about 80 activists from community groups and political activists from Sinn Féin, the (Trotskyist) Militant Labour, and the Workers Party. This campaign was ultimately successful. Charges were abolished before the 1997 general election. and it was decided that funding for water services was to come from general taxation with £50 million to be ring-fenced for water from motor taxes. But the battle to privatise Irish water was far from over.

In 1997 the Public Service Management Act was passed, which was designed to ‘modernise’ the entire public service by instituting a market-led technicist approach to operating public services that was strongly driven by business rhetoric and logic. People were seen as customers in a market, rather than citizens with rights.

Public Private Partnerships

Another aspect of the financialisaton of public resources relates to Public Private Partnerships (PPPs). Since the PPP model was first adopted in Ireland in 1999, projects in water treatment and wastewater have been the largest share of PPPs rolled out. Approximately, 63% of all PPPs in operation were contracted in the water sector and by 2008, Ireland, along with Greece had the second highest level of public/private operation of wastewater services in Europe (45%). PPP initiatives were favoured because they sat well with the right-wing myth that the market is more efficient than the state. Perhaps more importantly, they were debts that don’t show up on government balance sheets. The IMF, of all people, note that, “In many countries, investment projects have been procured as PPPs not for efficiency reasons, but to circumvent budget constraints and postpone recording fiscal costs of providing infrastructure services”. And they allow governments to take on projects in the short term while repayment is long-term. (Incidentally, following the Good Friday Agreement in Northern Ireland, Sinn Féin became particularly enamoured with Public Private Financing. In the early 2000s, SF Education Ministers signed off on 20 privately financed school buildings. Martin McGuinness stated that PFI offered “real potential for value for money solutions”.